Supporting Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students in the Classroom

This past summer, I was lucky enough to intern with an organization that highlights learner variability and supports educators in determining the most effective strategies to support their learners. After hosting two webinars about the variability within deaf students and intersectionality (check them out in Resources below), it became clear that educators were searching for information and resources on how to best serve their deaf and hard-of-hearing (HOH) students.

Over the last year, distance learning forced educators to completely reinvent lesson plans, contend with rushed technology roll-outs, and wrangle students’ attention in each virtual class session. This often meant that accessibility was not at the forefront, impacting many students with disabilities, particularly deaf and HOH students who rely heavily on American Sign Language (ASL), listening devices, lip-reading, interpreters, or speech-to-text services in their mainstream programs. For these students, the loss of a daily schedule, interactions with their classmates, and activities—on top of having unique communication needs—had a measurable impact.

To help educators better support deaf and HOH students, especially in distance learning settings, I interviewed two teachers to understand their experiences, challenges, and successes and share their feedback:

Meredith Lipman, a hearing preschool teacher at the Atlanta Area School for the Deaf who received her B.S. in ASL-English Interpreting and her M.A. in Early Childhood/Deaf Education.

Jesse Thomas, a deaf teacher at the Model Secondary School for the Deaf in Washington, D.C., who holds a B.A. in History and an M.A. in Deaf Education. He teaches Current Events and World Geography to grades 9-12.

What does it take for educators to better support deaf and HOH students?

First, it’s important to better understand deaf and HOH students themselves. Like all students, deaf and HOH students come from diverse backgrounds with different races, socioeconomic statuses, family dynamics, and personal experiences, and they all have unique learning needs. However, deaf and HOH students also present another unique aspect to their background: their language and communication needs. It is important to recognize that deaf and HOH students can demonstrate:

1 – Different types and ranges of hearing abilities

2 – Variable age of language acquisition

3 – Use of a range of assistive devices

4 – Individual communication preferences

5 – Varied preferences for language use

Knowing who students are and the accommodations they need will help educators develop more targeted supports that not only benefit deaf and HOH students, but all students in the classroom.

It is also important for educators to recognize their own biases to ensure all learners in the classroom receive equal access to educational content and classroom engagement. deaf students are more likely to be stereotyped and suffer discrimination in the classroom by peers and teachers alike, and this phenomenon is compounded when they are deaf students of color. This type of discrimination can contribute to the lower academic and life outcomes seen in the deaf population.

Being a more conscious teacher involves:

1 – Recognizing privileges and power in your role.

2 – Valuing deaf and/or Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) coworkers and paraprofessionals.

3 – Consciously incorporating cultural and language aspects in lessons.

4 – Providing opportunities for students to learn from each other and work together.

5 – Extending compassion and empathy when handling issues with students, and work with students to develop constructive solutions.

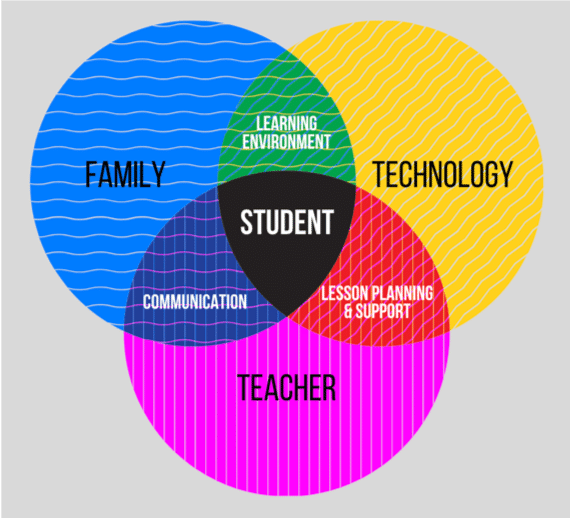

Another key aspect of virtual teaching is family communication. Understanding students’ learning environments and finding ways to build relationships with parents/caregivers can be instrumental, especially when they may have had negative educational experiences or feel hesitant to get involved in students’ learning. Lipman, for instance, extended her work phone number to her students’ families, which helped build rapport with them and made check-ins easier. Meanwhile, Thomas’ school has sent out newsletters in ASL, Spanish, and English to accommodate the language needs of their students’ families, and they offer meetings with provided accessibility for caregivers to voice their concerns and discuss issues with teachers.

For many students, a quiet and private learning space free from distractions may be difficult to find outside of school, and some may only have limited or shared access to technology for participating in class. With this in mind, Thomas worked with his students to troubleshoot technology issues and figure out creative work-arounds and alternative methods for them to complete assignments. Educators can also record classes and make all materials fully accessible on their online learning platform to make it easier for students to complete work on their own time.

Homework has also taken on a new meaning in distance learning. Rather than give busy work or lengthy assignments, teachers are assigning more meaningful and engaging homework with flexible due dates. Thomas emphasized that empathy and flexibility are key in his lesson plans and assignments. Making time for independent work, one-on-one support, and informal chats helps his students feel more comfortable seeking support in a virtual setting.

A few additional considerations for educators when assigning work:

1 – Don’t assume students will have materials to spare for activities. Survey your students to determine what learning materials they can use for class activities and tailor activities to the materials available to all students. You can also work with students to figure out alternative materials they can use for class.

2 – Determine if your school has alternate tutoring times where students can seek support if they are unable to attend during class time or have difficulty with assignments.

Another issue in virtual learning is “Zoom fatigue,” a feeling of exhaustion after participating in video calls and working on a computer for an extended period of time. Thomas recognizes this in his own classroom: “Zoom fatigue is the biggest [challenge]. For my students with language delays, the reduction of interaction time really hurts.”

These kinds of barriers to learning can contribute to a lack of motivation and lowered productivity in students. While no one perfect solution exists, the following suggestions from Thomas, Lipman and the National Deaf Center (NDC) can help:

1 – Make lesson plans as accessible as possible and modify approaches and activities through trial and error.

2 – Incorporate movement, creativity/imagination, and teamwork into your lessons. Use breakout rooms to divide students into small groups.

3 – Minimize visual demands and clutter. Multitasking demands are higher on deaf students, as they must attend to interpreters or assistive devices in addition to the same visual information hearing students are presented with.

4 – Brain breaks or movement breaks help to refocus students and transition between content areas.

5 – Poor internet connections can disrupt students’ learning and comprehension of materials. All video representations of the audio stream should be recorded and available at any time on education platforms.

The distance learning transition was and is tough for all teachers, no matter the grade level or content area. Fully remote teaching comes with new challenges each day, and many teachers struggle to balance their already-heavy workload with a shift in their teaching approach. As Lipman noted, “Sometimes it feels like throwing spaghetti at a wall, trying to figure out what will stick with them. Some days one approach works, some days it doesn’t.”

For teachers of deaf and HOH students who are additionally struggling to replace hands-on, tactile activities and ensure that all activities are accessible for their students, this challenge can be draining. Thomas and Lipman recommend these coping strategies:

1- Discuss issues with a fellow teacher.

2 – Attend webinars aimed at creative solutions to virtual learning.

3 – Find a group of teachers with similar challenges to contribute ideas, offer support, and troubleshoot issues.

4 – Set aside personal time to read, meditate, exercise, or cook a meal.

5 – Take micro-breaks, especially to alleviate eye strain.

6 – Set boundaries to maintain a work-life balance.

Ultimately, patience, compassion, and flexibility are key. Educators should collaborate with deaf and HOH students to find creative solutions for better distance learning, keeping in mind that accessibility should be the default, not the compromise.

Note from the author: While mentioning those in the deaf community throughout this document, it has stated with a lowercase ‘d’ as deaf, as a capital D typically refers to students who are culturally deaf and feel a strong connection with the culture, whereas little d deaf typically refers to the more general population of deaf individuals. This document decided to include the many deaf individuals who do/do not identify with deaf culture as deeply as some others do.