This article was written and Published by Linda Jacobson— October 10th, 2024

The response topped a goal for 250,000 — 9 months early — but the effort’s future depends ‘100% on the election,’ one leader said.

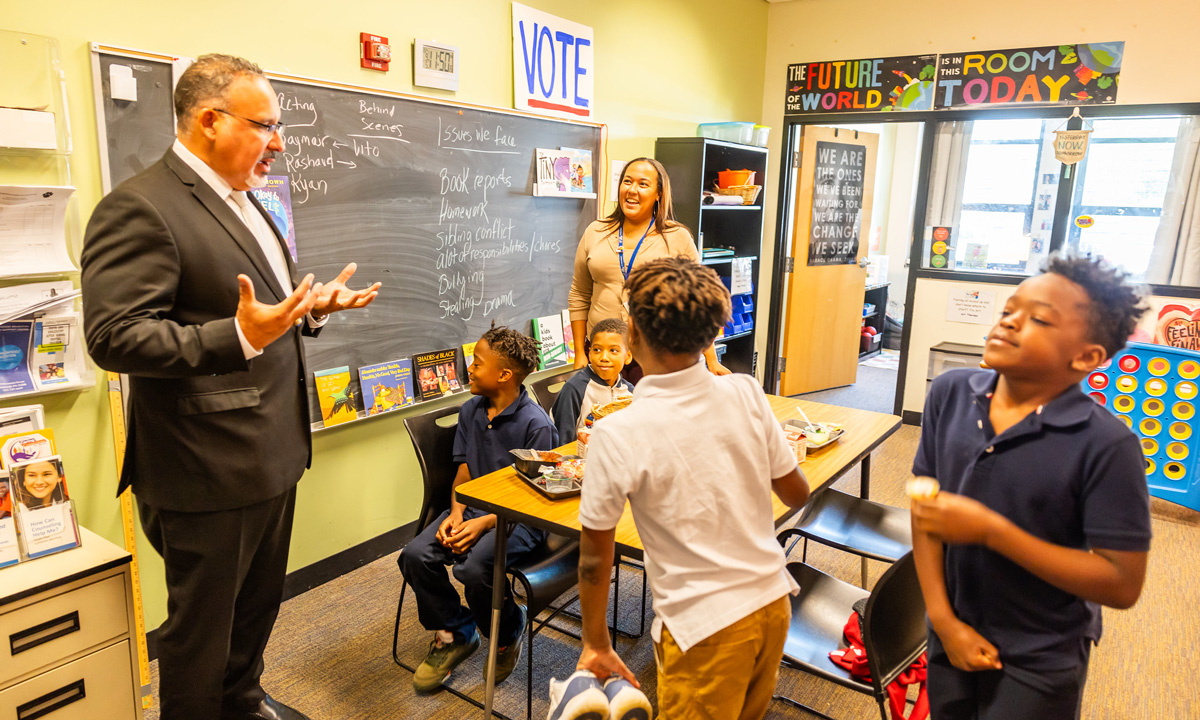

U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona visited Faison K-8 School in Pittsburgh during his fall bus tour last month. (U.S. Department of Education)

U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona visited Faison K-8 School in Pittsburgh during his fall bus tour last month. (U.S. Department of Education)

In 2022, the Biden administration called for 250,000 tutors and mentors to rescue what some have called the pandemic’s “lost generation.”

The White House, which has faced criticism for not doing enough for students who fell dramatically behind in math and reading, had something to show for it Thursday. An estimated 323,000 college students, volunteers and school staff signed up — not only exceeding the administration’s goal, but hitting it nine months ahead of schedule.

President Joe Biden called for Americans to volunteer as tutors and mentors during his 2022 State of the Union address. (Jim Lo Scalzo-Pool/Getty Images)“This problem is not getting solved by somebody in Washington D.C. We launched the vision. We sent out money,” Deputy Secretary of Education Cindy Marten said at an event to celebrate the milestone. But those resources, she said, “helped to galvanize” volunteers and staff at the local level. “I’m proud that we can see the results of this collective effort.”In the 2023-24 school year, over a quarter of principals reported offering more tutoring, mentoring or other support services than they did the previous year, according to a survey of over a thousand school leaders released ahead of the event. In all, roughly 24,500 schools added an average of 5.5 additional adults focused on supporting students.While it’s too early to determine what effect the extra help had on student performance, over 30% of principals said they were able to employ research-backed, high-dosage tutoring, according to the survey from the Rand Corp. That means trained tutors worked with the same students over time for at least 90 minutes per week.

President Joe Biden called for Americans to volunteer as tutors and mentors during his 2022 State of the Union address. (Jim Lo Scalzo-Pool/Getty Images)“This problem is not getting solved by somebody in Washington D.C. We launched the vision. We sent out money,” Deputy Secretary of Education Cindy Marten said at an event to celebrate the milestone. But those resources, she said, “helped to galvanize” volunteers and staff at the local level. “I’m proud that we can see the results of this collective effort.”In the 2023-24 school year, over a quarter of principals reported offering more tutoring, mentoring or other support services than they did the previous year, according to a survey of over a thousand school leaders released ahead of the event. In all, roughly 24,500 schools added an average of 5.5 additional adults focused on supporting students.While it’s too early to determine what effect the extra help had on student performance, over 30% of principals said they were able to employ research-backed, high-dosage tutoring, according to the survey from the Rand Corp. That means trained tutors worked with the same students over time for at least 90 minutes per week.

President Joe Biden called for Americans to volunteer as tutors and mentors during his 2022 State of the Union address. (Jim Lo Scalzo-Pool/Getty Images)

President Joe Biden called for Americans to volunteer as tutors and mentors during his 2022 State of the Union address. (Jim Lo Scalzo-Pool/Getty Images)

“This problem is not getting solved by somebody in Washington D.C. We launched the vision. We sent out money,” Deputy Secretary of Education Cindy Marten said at an event to celebrate the milestone. But those resources, she said, “helped to galvanize” volunteers and staff at the local level. “I’m proud that we can see the results of this collective effort.”

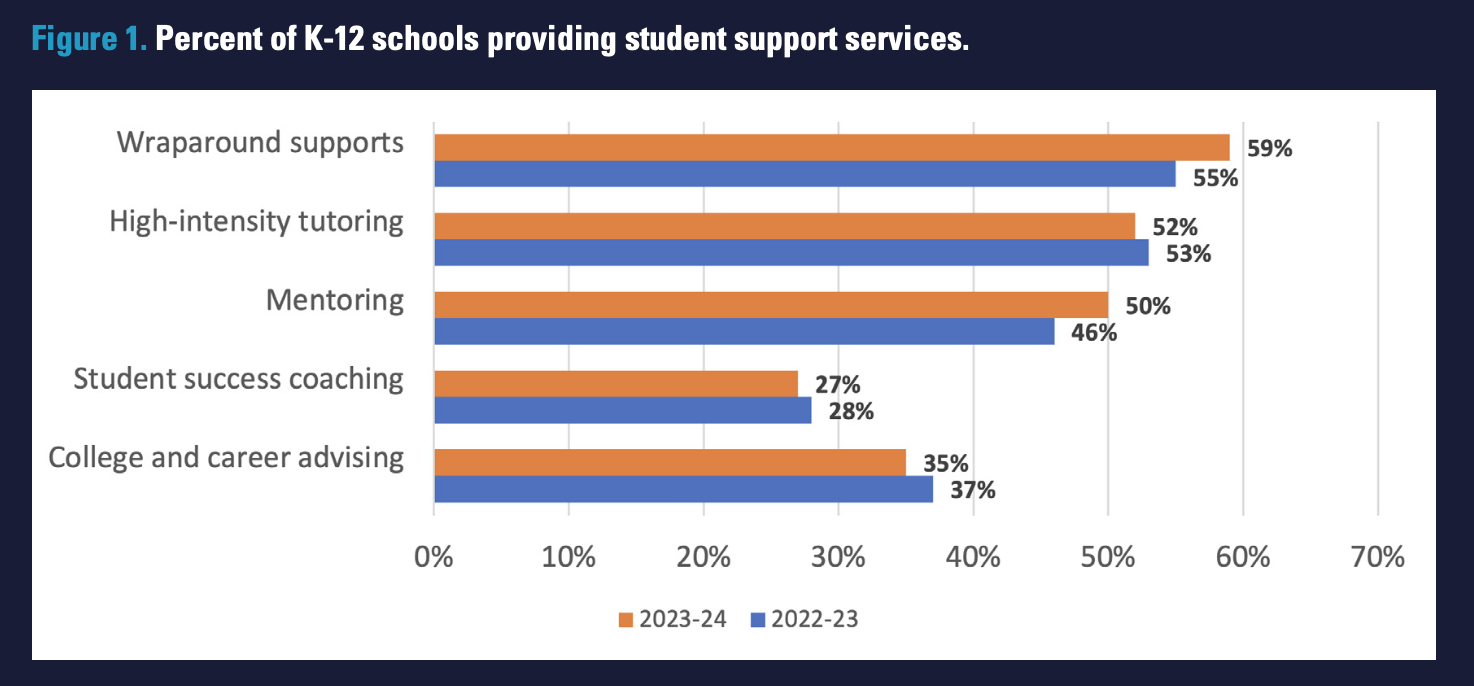

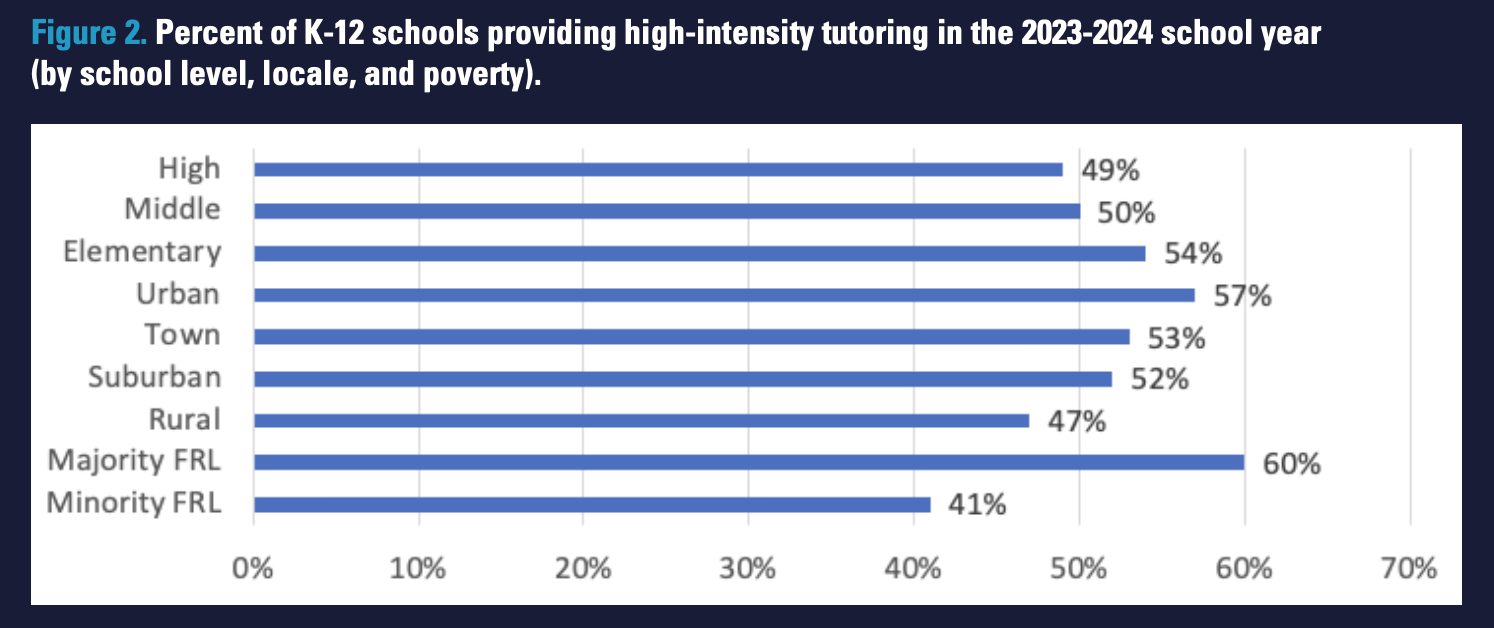

In the 2023-24 school year, over a quarter of principals reported offering more tutoring, mentoring or other support services than they did the previous year, according to a survey of over a thousand school leaders released ahead of the event. In all, roughly 24,500 schools added an average of 5.5 additional adults focused on supporting students.

While it’s too early to determine what effect the extra help had on student performance, over 30% of principals said they were able to employ research-backed, high-dosage tutoring, according to the survey from the Rand Corp. That means trained tutors worked with the same students over time for at least 90 minutes per week.

Demand for tutors has received significant national attention, given students’ steep decline in learning. But the White House count also reflects a variety of added positions, including mentors to help re-engage chronically absent students and those who help students navigate college applications. About $20 million in federal relief money, flowing through AmeriCorps, the national service organization, fueled the partnership’s work. Districts also dipped in to other COVID funding to support the extra positions.

But the initiative, led by the National Partnership for Student Success at Johns Hopkins University, faces an uncertain future. Districts are using up what’s left of that money, and Republicans want to slash funding for AmeriCorps, as they have for years.

“One hundred percent depends on the election,” said Robert Balfanz, the Johns Hopkins professor who leads the partnership. He expects the effort to continue “in some form” if Vice President Kamala Harris wins.

It’s unclear whether Donald Trump would do the same, but the educational effects of the pandemic will linger regardless of who’s in office, he said.

“We have kids that are disengaged. We have kids that have greater out-of-school problems. We have kids that are more confused about what they want to do after high school,” Balfanz said. “It’s very hard to address those kids with your school staff alone.”

Launched six months after U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona issued the charge for more tutors, the initiative serves as a hub for connecting local groups and individuals to schools that need them. Some leaders from the partnership’s national network of 200 districts have tried new strategies to motivate students.

In hopes of reducing a chronic absenteeism rate of about 30%, Principal Scott Hale at Johnstown High School, north of Albany, New York, tapped existing staff members, like teaching assistants, secretaries and coaches, to serve as mentors.

“Success mentors” at the school are matched with students to better understand why they’re absent and what incentives might lure them back. Keeping track of absences on a simple paper calendar drives home how quickly they can add up, Hale said.

“Many students don’t realize how many days they have missed until they see it,” he said. Reducing schoolwide chronic absenteeism has been tough, he added. But over half of the 125 students with mentors increased their attendance. “To see a kid improve from 80 absences to 30 is a huge win for us.”

‘Must be doing the right thing’

College students, who saw their own educations disrupted by the pandemic, have been integral to school recovery efforts, said Josh Fryday, chief service officer for California Volunteers.

“This generation experienced COVID in high school,” Fryday said. “I think they understand how important it is to be connected and have this extra support.”

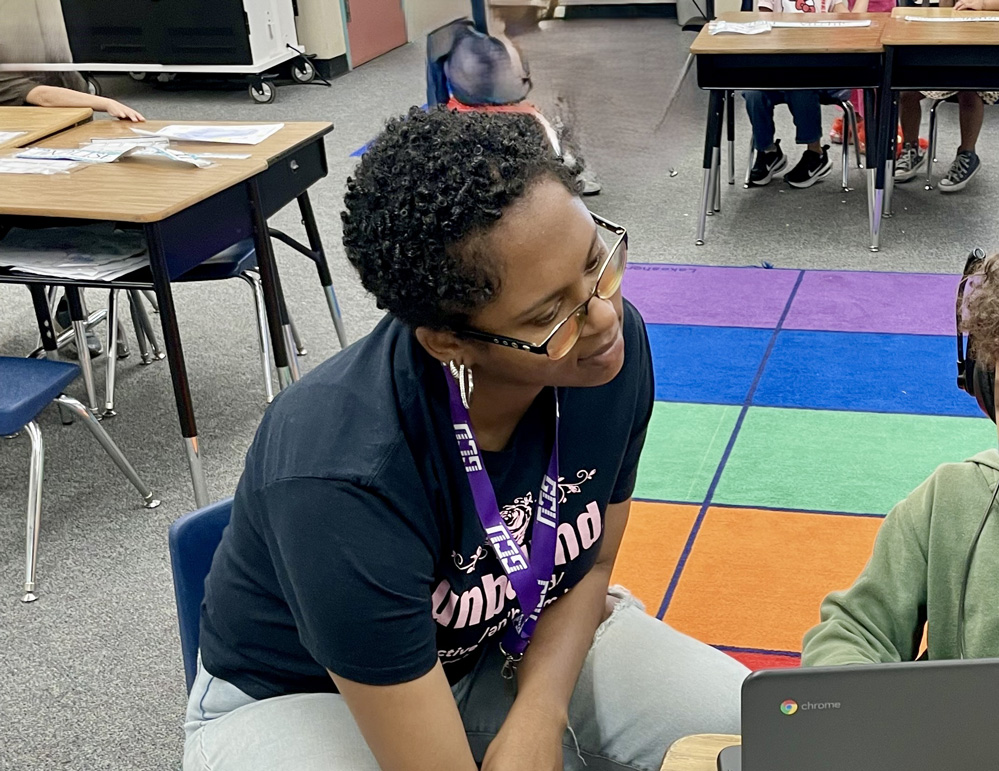

Devin Blankenship was among those who signed up for the organization’s College Corps. She was earning a degree in sociology from Vanguard University, south of Los Angeles, and wanted some nonprofit experience. To avoid commuting through Los Angeles traffic, she took a virtual tutoring position with Los Angeles-based Step Up Tutoring.

Over the next year, she worked with a third grader from the Los Angeles Unified School District whose reading skills had been so severely impacted by school closures that he barely knew letter sounds. Before she could focus on a lesson, another student confided in Blankenship about getting bullied at school.

“Students told me they were excited to come to tutoring for that hour,” she said. “I said, ‘Wow, I must be doing the right thing.’ ”

Blankenship’s experience also points to some of the challenges tutors have faced, especially in a district as large as Los Angeles. At times, she didn’t know where to go with questions about helping a student or working with a family. She said she had to initiate Zoom or phone calls with her supervisor for answers.

There were also moments when she felt ill-equipped to help. She recalls watching YouTube videos on improper fractions late at night while trying to meet a midnight deadline for a college paper.

“I was like, ‘Man, I wish there were tutoring sessions for me,’ ” she said.

With interest in a career in education, she sometimes felt frustrated that she didn’t have more interaction with students’ teachers. But those limitations didn’t drive Blankenship away. She now works as a teaching assistant in a special education class at Palms Elementary School in Perris, California, east of Los Angeles. She’s part of a program that fast-tracks interns into classroom positions to help address a teaching shortage.

‘Solved the problem’

In addition to giving future teachers practical experience, the national effort has spawned connections between tutoring organizations and college students looking for work.

Pepperdine University in Malibu, California, struggled while schools were closed to find community service jobs for its students. Then an official who runs its federal work-study program learned about Step Up Tutoring through a local TV news segment.

Pepperdine was “really interested in partnering with Step Up because we solved the problem for them,” said Sam Olivieri, Step Up’s CEO. “We were able during COVID to fill those community service slots through a virtual program.”

Word of their partnership spread and Step Up Tutoring now draws college students from 17 institutions. Virtual tutoring options have helped universities meet Cardona’s 2023 challenge for higher education leaders to spend 15% of their work-study funds on community service — more than double the minimum of 7%.

Olivieri thinks that the higher commitment from colleges to helping K-12 students will be a “durable” impact of the partnership’s work.

Rand’s data shows that despite the additional funding and personnel, a third of principals said only some of the students who needed the services received them.

“The waters are not receding,” Balfanz said at the event. “The challenge remains.”