This article was written by Kevin Mahnken on December 12, 2023, and published by The 74.

Schools had one foot in the shutdown era, still struggling to restore a sense of normalcy that disappeared in 2020. A steep rise in behavioral and disciplinary issues, which many teachers hoped would be only the temporary product of COVID’s generational disruption to routines, stayed with us. Millions of kids have remained separated from their local schools — not because they’re prevented by public health measures from entering the building, but because they’re simply choosing not to attend classes. And across a whole range of academic subjects, actual student learning is lower and slower than it was before the pandemic.

Meanwhile, school systems are adapting to trends and technologies that have arisen just over the past few years. Districts are spending billions of dollars to establish or expand tutoring programs, which may be America’s best tool to combat learning loss, while AI platforms like ChatGPT are transforming the way instruction can be delivered (and challenging schools’ ability to keep ahead of cheating).

And researchers continue to ask all the questions that have traditionally set the parameters of America’s K–12 agenda: Why do student populations self-segregate? Is it better for kids to be assigned to tough or easy graders? How much do teacher training programs really help? Have charters caught up to traditional public schools?

As we do every year, The 74 has compiled a year-end inventory of the most fascinating discoveries, insights, and ambiguities that came out of education research in 2023.

Welcome to the year in charts.

Student absenteeism is out of control

You could spend a lot of time simply tallying the aspects of student life that COVID made worse: significantly diminished achievement, lower odds of graduating on time, escalating behavioral challenges, and fewer applications to college. But the most dangerous consequence might be its effects on how often children came to school.

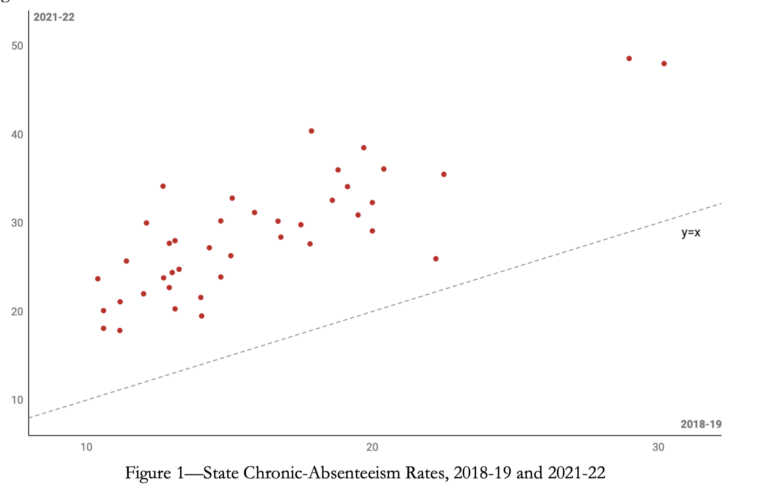

According to data collected by Stanford University Professor Thomas Dee, the proportion of K–12 students who were chronically absent — i.e., who missed 10 percent or more of the school year — nearly doubled during the pandemic, vaulting from 14.8 percent in 2019 to 28.3 percent in 2022. Extrapolated across all schools, that means an additional 6.5 million kids became chronically absent following COVID. Every state Dee studied saw an increase of at least 4 percentage points, but those with higher pre-pandemic rates of absence experienced the largest jumps.

The findings jibe with those of other alarming research on attendance. An analysis from Johns Hopkins University’s Everybody Graduates Center and the advocacy group Attendance Works, covered by The 74’s Linda Jacobson in October, showed that in 2021–22, two-thirds of American students attended a school where at least 20 percent of students were chronically absent. In over half of all high schools, chronic absenteeism rates topped 30 percent that year.

Catch-up learning hit a wall last year

But are kids (at least, the ones actually showing up) regaining the ground they lost since 2020? According to much of the testing data that emerged this year, the answer is no — or at least, nowhere near quickly enough.

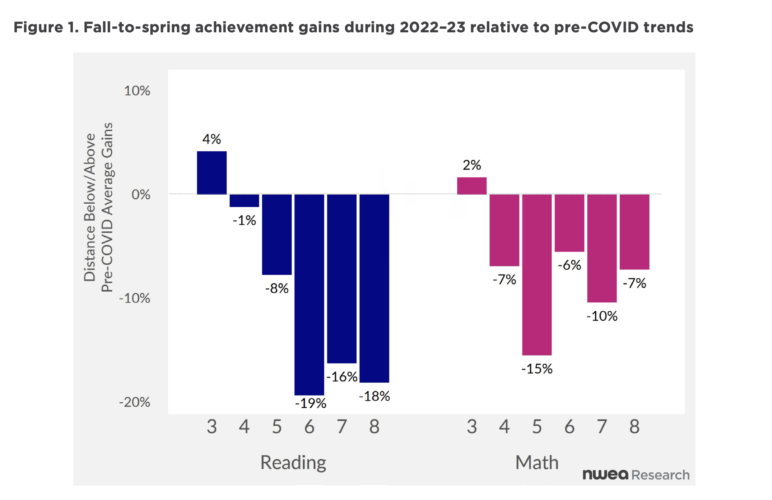

In a July report, researchers from the nonprofit testing organization NWEA combed through nearly seven million children’s scores on the Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) assessment, which is administered both in the fall and the spring to measure how much students learn during the year. But test takers in the 2022–23 academic year made markedly less progress in key subjects than comparable elementary and middle schoolers who sat for the exam before the pandemic, with growth in reading and math falling by as much as 19 percent and 15 percent, respectively. Only third-graders exceeded the pre-COVID learning averages.

The stalled momentum was directly cited in the Center on Reinventing Public Education’s dispatch on “State of the American Student,” which distilled a host of worrying trends and warned that America has little time left to reset the trajectory for millions of adolescents. According to ongoing indicators like the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which released long-run scores for 13-year-olds this spring, average performance in math and reading has been set back to levels last seen decades ago.

Even if schools and families feel like they’re through with the pandemic, the pandemic — and the harsh blow it has dealt to kids — isn’t done with us.

Virtual tutoring can work

Thankfully, states and districts aren’t sitting on their hands in the face of learning loss. Supported by billions of dollars of federal funds, many have invested heavily in tutoring programs that promise to help struggling children overcome the challenges imposed by past school closures and virtual instruction. The question is whether those efforts work for enough students to justify their cost — and according to data generated by the National Student Support Accelerator, a Stanford initiative devoted to studying the effects of tutoring, there is reason for hope.

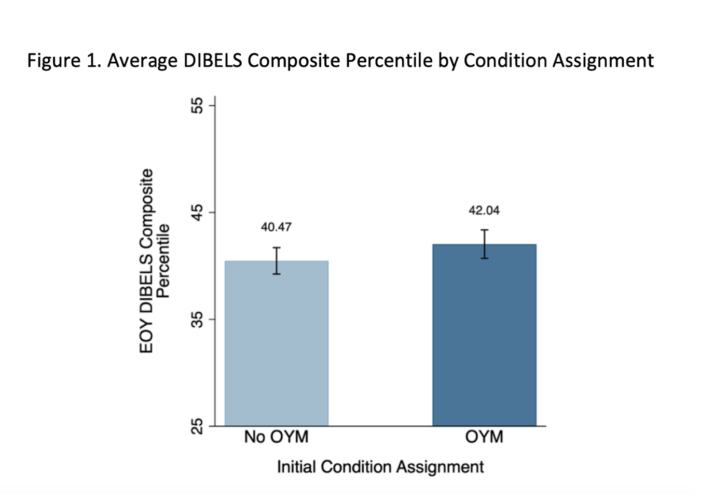

In October, the Accelerator circulated a paper showing impressive results from OnYourMark, a fully virtual program provided to developing readers. The study found that among 1,000 students enrolled in Texas charter schools, participating in OnYourMark resulted in kindergartners gaining the equivalent of 26 extra days of learning in letter sounds and first graders receiving 55 additional days of sound decoding. The news is particularly encouraging in that it shows a path to success for virtual tutoring, which has often been shown to be far less effective than in-person instruction.

Grade inflation got worse during the pandemic

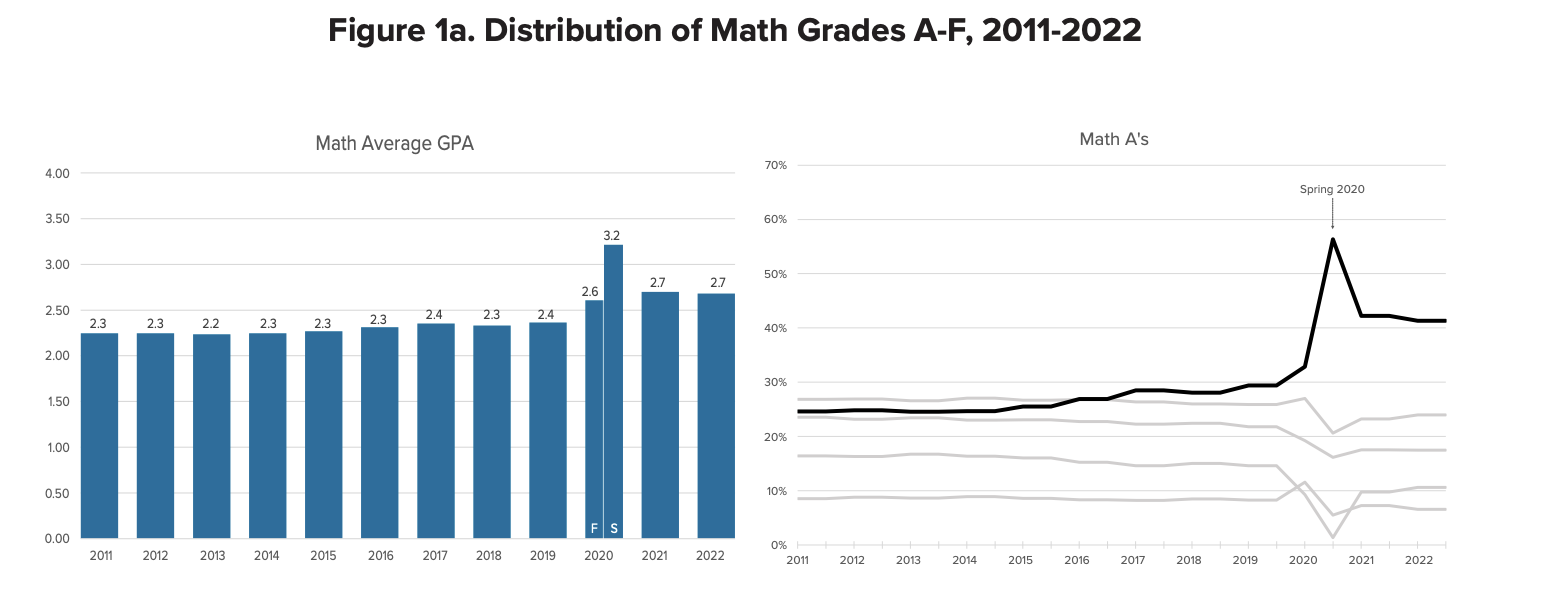

As the chaotic transition to online learning got underway in 2020, schools had to decide how they would judge the work of students cut off from their teachers and classmates. Many opted for more lenient policies, including eliminating F grades and granting credit for late or incomplete work, out of a desire to avoid more punitive measures during a crisis.

It’s difficult to chart the average impact of the shift across thousands of school districts, but the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER) recently released a brief focusing on a decade of student records in Washington State. The picture was stark: While the average middle and high school GPA for math rose by 0.11 points between 2011 and 2019, it got a boost three times that size — one-third of a GPA point, or about the difference between a C-plus and a B-minus — between 2019 and 2021.

In general, wrote CALDER director and American Institutes for Research vice president Dan Goldhaber, the relationship between student grades and their scores on state standardized tests “has diminished over time,” particularly in math. A similar pattern is suggested by the annual release of ACT results, which show scores remaining largely flat in recent years even as students’ self-reported high school grades have climbed. And just like with price inflation, GPAs that soared during the pandemic still haven’t fully come back to earth.

Tough grading has its advantages

So what are the effects of higher course marks? Several papers released this year indicate that they can be surprisingly negative.

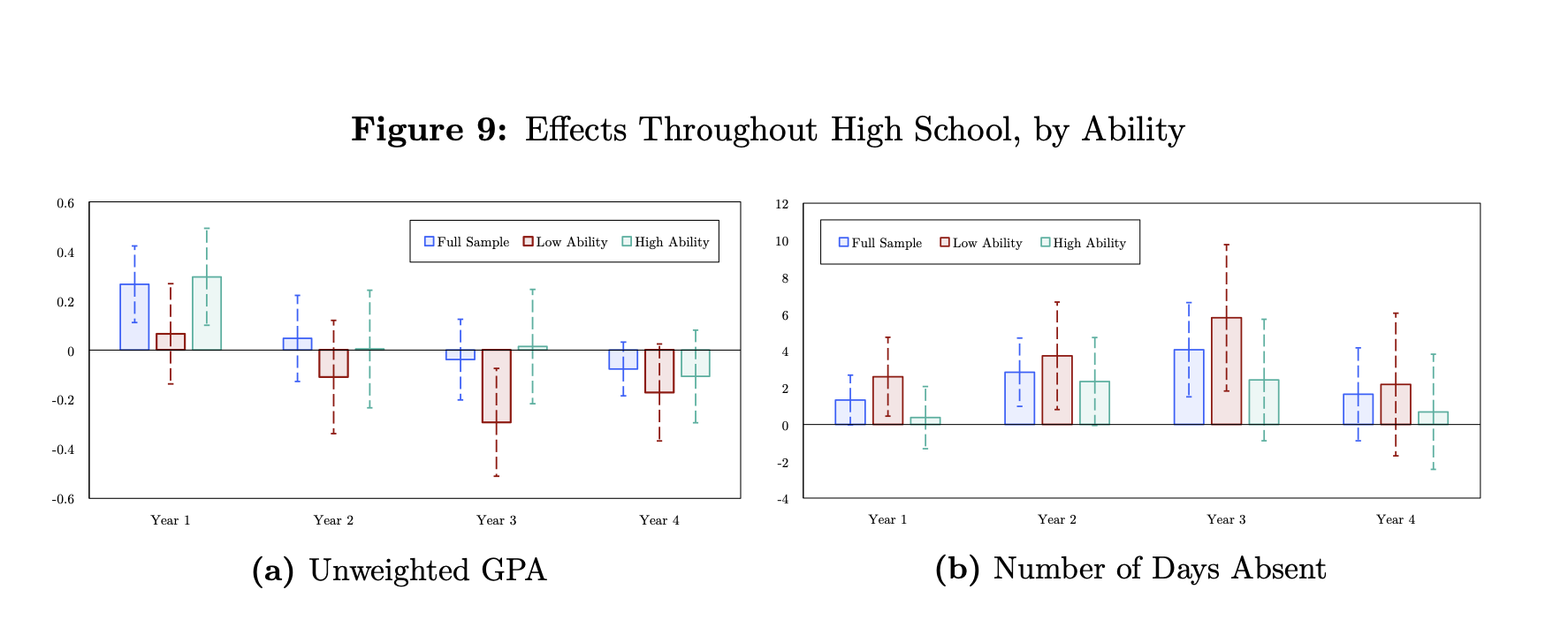

In a paper circulated this fall, a trio of researchers explored the consequences of a statewide switch to more lenient grading standards undertaken in North Carolina in 2014. The policy was meant to make grades more comparable between school districts, but in effect, it also lowered the threshold for each letter grade in high schools. It also seemed to affect various student groups quite differently. As expected, the highest-achieving kids received higher grades (though only in their freshman year), but disturbingly, struggling students didn’t receive a similar bump. They also seemed to disengage from school, accruing substantially more absences than students who weren’t exposed to the looser standards; over time, those absences likely hurt their learning, as measured by relatively lower scores on the ACT.

If easier grading holds the potential to hurt attendance and widen achievement gaps, the opposite may also be true. In a study that also focused on North Carolina schools, American University Professor Seth Gershenson discovered that eighth and ninth graders assigned to math teachers with relatively tougher grading standards later saw higher math scores throughout high school. And far from validating fears that hard classes make kids tune out, those students were also less likely to be absent from class than their peers.

COVID hit social studies too

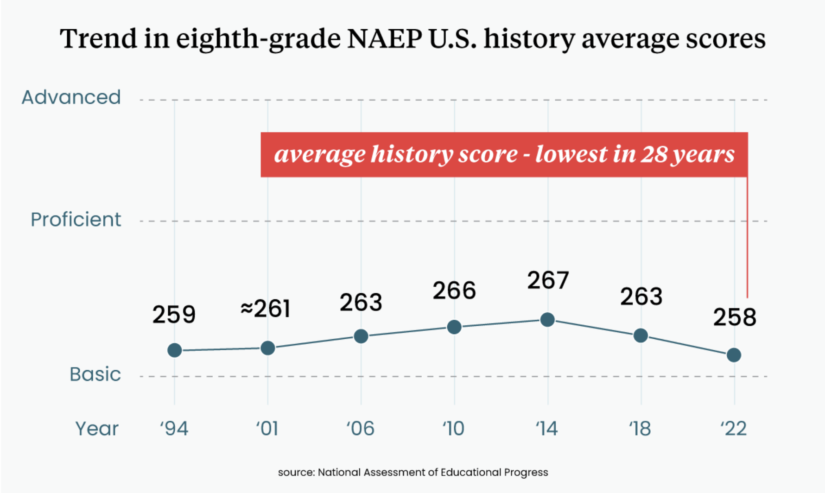

Much of the concern over learning loss is focused on weakened performance on the core disciplines of math and reading. In fact, the academic harm was widely dispersed.

The National Assessment of Educational Progress — a federal standardized test often called the Nation’s Report Card — only measures proficiency in social studies every four years. The exam’s latest results, revealed in May, showed that eighth graders’ average history scores fell by five points; civics scores fell by two points, the first decline in the history of the test. All told, the results for both have fallen to levels last seen in the early 1990s, the latest evidence that COVID has triggered a generational reversal in knowledge acquisition.

The swoon came amid a national debate over how to teach about American history and government, with states like Virginia initiating significant overhauls of their academic standards. But the phenomenon appears to be international in scope: Results from the International Civic and Citizenship Education study, which tests over 80,000 eighth graders across 22 industrialized countries on civic knowledge, showed that large numbers of test takers couldn’t answer questions about election fairness or democratic governance. Only 55 percent of respondents said they felt their nation’s governmental system “works well.”

Choice might be good for public schools

The explosive growth of school vouchers and education savings accounts, which allow families to spend public funds on private education, has dominated the school choice debate this year. Public school choice (i.e., charters and open enrollment policies), while also controversial, has receded somewhat from conversation.

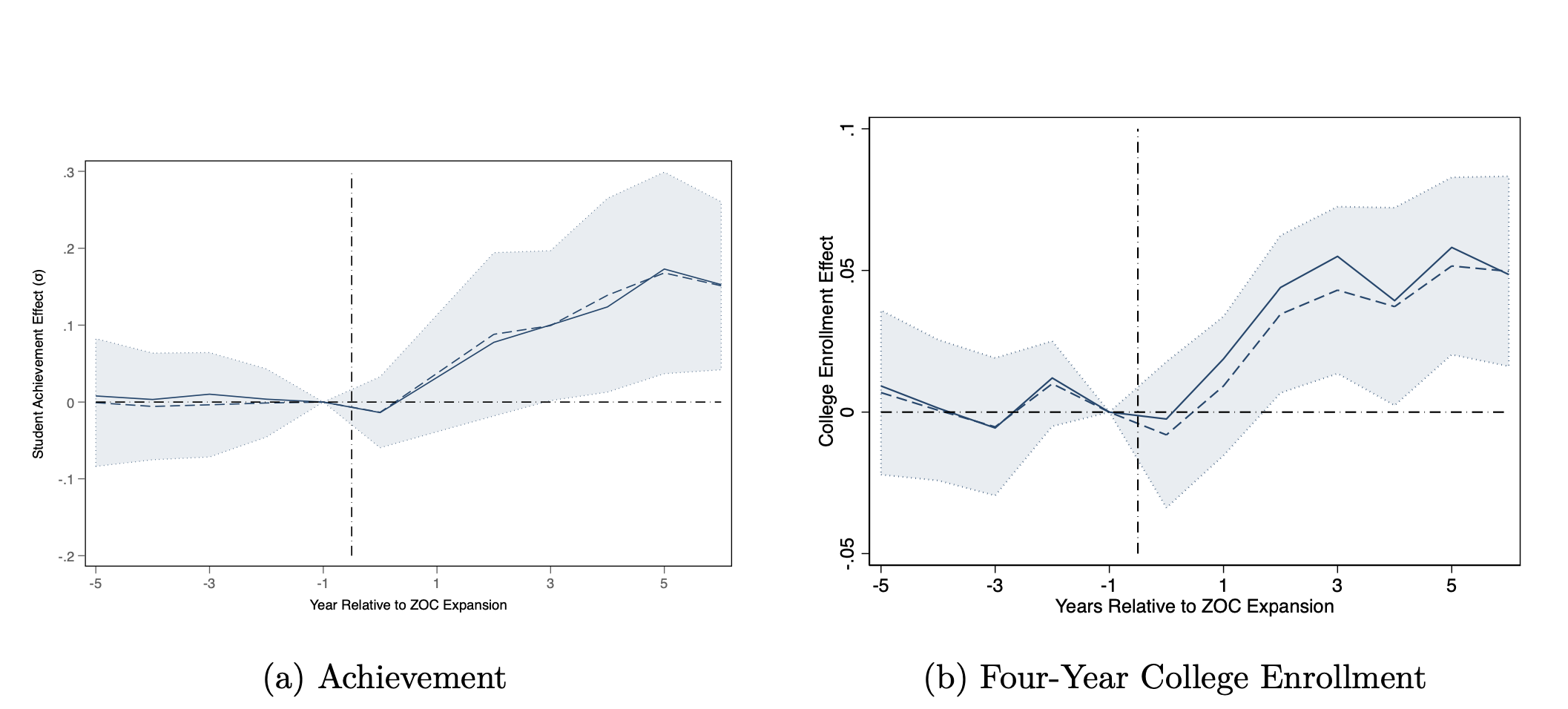

But a working paper released this summer indicates that, in addition to providing more instructional options to families that want them, intra-choice can improve learning throughout wider communities. University of Chicago economist Christopher Campos and data scientist Caitlin Kearns scrutinized Los Angeles’s Zones of Choice initiative, which allows families within designated neighborhoods to select among multiple high schools rather than send their children to the one nearest their home. Participation in the program, they learned, significantly increases students’ English exam scores and boosts their enrollment rate at four-year colleges by 25 percent. Those gains were concentrated among schools exposed to the most competition and those that previously performed the worst, strongly hinting that inclusion in the Zones pushed them to hold onto students by improving their offerings.

A different study of choice in North Carolina yielded broadly similar results, though with caveats. Focusing on the state’s decision to lift its cap on charter schools in 2012, the paper’s authors revealed that the move incrementally improved public schools’ value-added scores as measured by state standardized tests; that improvement, while small in scale, generated huge value in the aggregate, as the study concluded that the average public high schooler’s lifetime wages were lifted by $1,500 by allowing more charters to open. As in the Los Angeles study, the promising effects seem to have come about through competition for students.

Dispiritingly, however, the impact on pupils who actually enrolled in the charter schools after the cap was lifted was negative, perhaps because the newly established schools tended to employ more “non-traditional” models (e.g., project-based or experiential learning, such as Montessori) that weren’t as successful as existing charter options.

No one said this stuff was simple.

Charters aren’t underperforming anymore

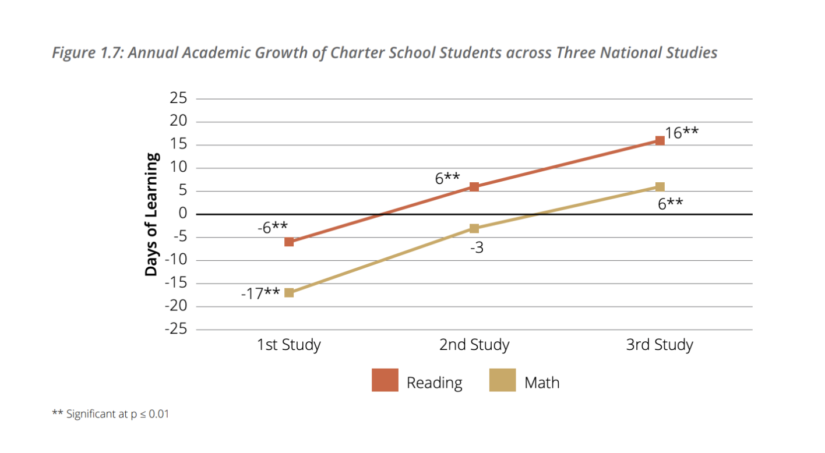

Charter schools have been around for over 30 years. For most of that time, their advocates and detractors have argued passionately over just how effective they really are at improving academic achievement. The primary arbiter of those disputes, most often, has been Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO), which has released a series of studies over more than a decade comparing the performance of charter students with those enrolled at district public schools.

In the first few editions, those reports showed the newer schools lagging behind their traditional counterparts — evidence that the sector’s opponents’ cited frequently throughout the fierce school reform battles of the Obama era. But the latest iteration — CREDO’s first national evaluation in a decade, including data on 1.8 million students across 31 states and cities — calculated that charter students receive the equivalent of 16 extra days of learning in literacy, and six extra days of math, than students at the local public schools they would have otherwise attended. The edge, while decidedly slight, masks larger variation among subgroups: Black students gained an average of 35 extra days of reading growth and 29 extra days of math, equal to more than a month of supplemental instruction.

Not all charters are created equal, however. An article published last month in the journal Education Next, and covered by The 74’s Greg Toppo, compared the performance of charter sectors in each state based on their students’ performance on NAEP. Somewhat surprisingly, the state with the top showing was Alaska, where charter students score an average of 32 points higher on the test than the national average for charter school students. Their peers in Pennsylvania, Oregon, Michigan, Tennessee, and Hawaii weren’t so fortunate, with each scoring at least 21 points lower than the national average.

Teacher prep can be rethought on the fly

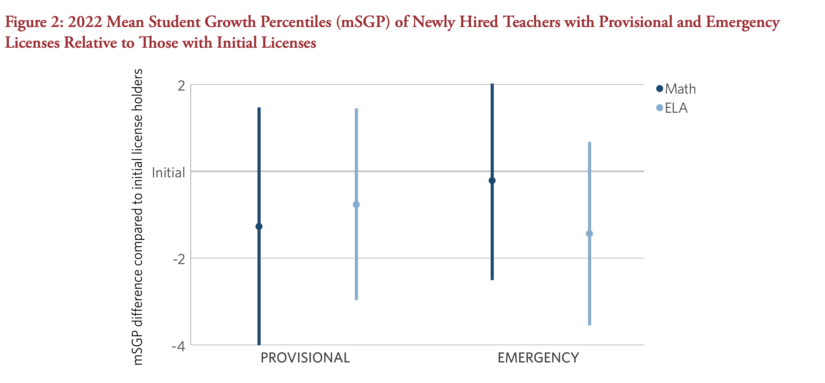

Starting in spring 2020, Massachusetts launched a grand experiment: Concerned that the tumultuous working conditions of the pandemic would discourage young people from becoming teachers, the state began issuing emergency credentials to teaching candidates even if they hadn’t completed the necessary coursework to be licensed. Over the next three years, almost 20,000 such licenses were granted to instructors who worked full-time while simultaneously working to meet their licensure requirements.

Boston University’s Wheelock Education Policy Center has followed the progress of those early-career teachers. Their analysis, laid out in multiple reports, presents a quietly stunning observation: As measured through a combination of school-level performance evaluations, principal questionnaires, and student scores on standardized tests, the emergency-licensed teachers perform similarly to their colleagues who completed traditional teacher preparation programs. Students assigned to them were not disadvantaged in learning in spite of their unconventional path to the classroom. What’s more, by the program’s second year, one-quarter of emergency licensees were non-white — vastly more than the statewide average in Massachusetts.

The notion that aspiring educators can thrive in the profession without reaching it through the traditional channels isn’t a new one; Teach for America and other alternative credentialing programs have existed for decades, yielding some real successes during that period. But the Massachusetts experience illustrates some of the specific benefits of dropping licensure requirements during a crisis. Namely, making entry more flexible (and shaving off the years of study and thousands of dollars in tuition that often act as a deterrent to otherwise qualified candidates) can produce a more diverse and no less effective workforce.

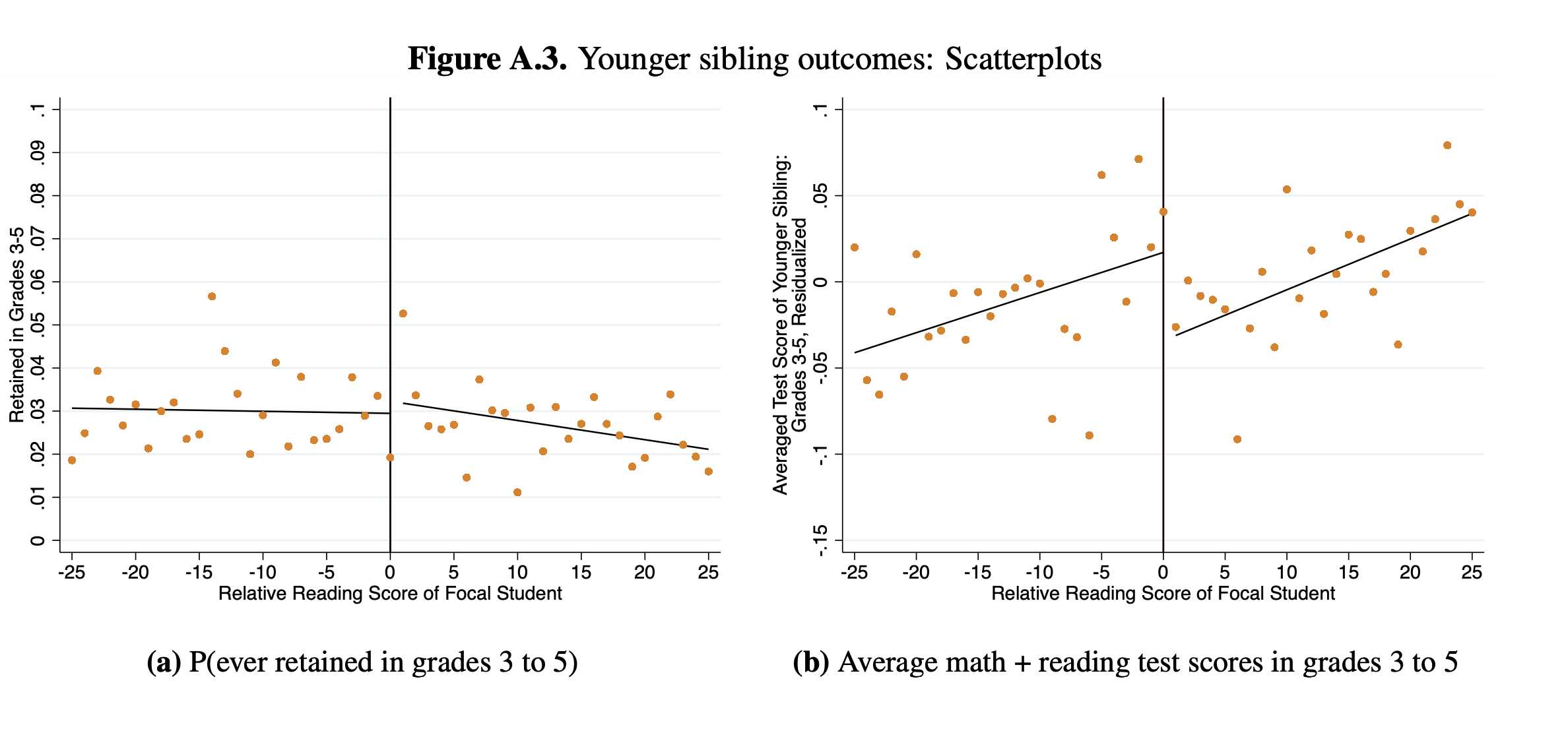

More good news on third-grade retention

Legislation around the science of reading has swept through dozens of states over the last decade. In part, the political success of the new literacy agenda is due to the popularity of most of its planks: evidence-backed curricula, teacher coaching, and additional resources for kids and schools that need them.

By contrast, third-grade retention — holding back students for a year if they’re not on track to succeed by the end of that crucial threshold — plays the role of the bad cop. In spite of the existing evidence that struggling elementary schoolers in states like Florida and Indiana can see large benefits from repeating a grade, many parents and teachers still consider that step too punitive.

But according to a paper circulated in June, the upsides of the approach extend in some unexpected directions. In a study of 12 large school districts in Florida, which has had a retention policy related to reading scores for over 20 years, researchers found that third graders made significant gains in scores for both math and reading after being held back. Even more promising, targeted students’ younger siblings also saw larger learning gains than the brothers and sisters of comparable students who weren’t retained.

It’s unclear what feature of Florida’s law led to the positive “spillover effects,” but study co-author Umut Özek told The 74 that families might be responding in an advantageous way to the experience of their older children. “When you get a signal that says, ‘Your kid is not performing at a level that will allow them to be promoted to fourth grade,’ that’s a very clear signal that will likely induce a response from parents.”

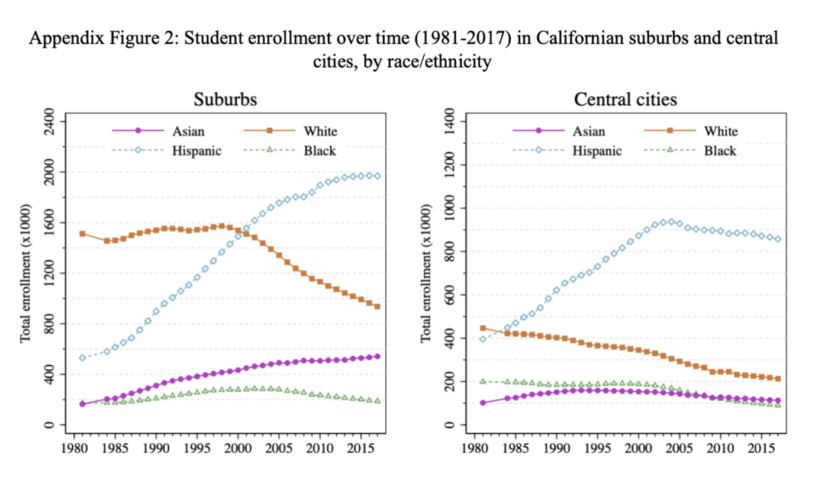

Asian students in, white families out

“White flight,” as it’s usually understood, refers to the phenomenon of working- and middle-class white families decamping from inner cities in the 1960s and ‘70s as a response to increased crime, deteriorating local economies, and growing numbers of African American residents. It’s a hotly contested phenomenon, but many in the education policy world blame it for contributing to school segregation and shrinking the tax base of urban school districts.

This year, superstar researcher Leah Boustan applied the concept to a different setting. A student of prior racial migrations at the city level, the Princeton economist studied the movement of Asian-American students into 152 California school districts, all of them suburban and relatively affluent. The sizable growth over the decades of the early 21st century appeared to generate its own version of white flight — more specifically, for every Asian student who enrolled in local schools, 1.5 white students left.

The departures weren’t correlated with any other demographic changes. But accompanying survey evidence convinced Boustan and her collaborators that they also likely weren’t triggered by racial animus. Instead, they pointed to white parents’ wariness of academic competition with Asian-American kids, who out-achieve other student categories in virtually every academic metric.

“Someone is showing up in the district who scores better than they do,” Boustan said in an interview with The 74. “In relative terms, the white kids are generally falling behind.”

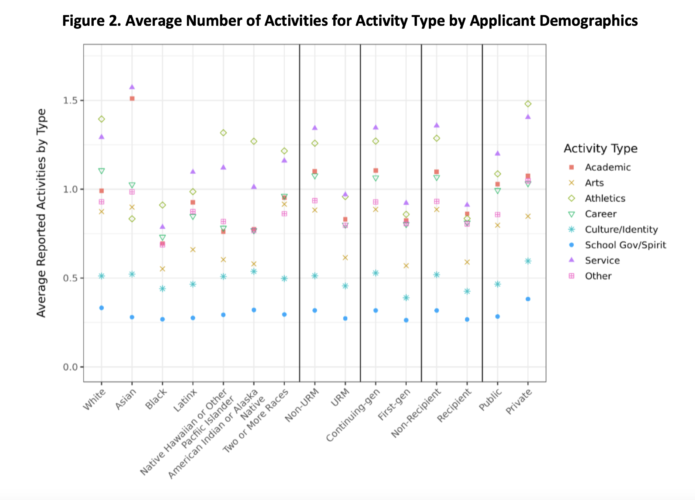

Extracurricular activities show large racial gaps

The most significant education development of 2023 may well have been the Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, the case that prohibited the use of racial preferences in college admissions. The end of affirmative action as we’ve known it, occurring just as colleges move en masse away from the use of entrance exams like the SAT and ACT, means that admissions decisions will increasingly be made on the basis of other parts of the application package.

One of those will undoubtedly be extracurricular activities — the menu of clubs, productions, athletics, and volunteer opportunities that high schoolers have learned to embrace in order to be considered well-rounded. But if their aim is to foster diversity while adhering to new legal constraints, colleges might think twice before relying on them too heavily. According to an April study drawing on nearly 6 million college applications from the 2018–19 and 2019–20 admissions cycles, participation in extracurriculars is surprisingly race-specific. White, Asian-American, and wealthy students, along with those attending private high schools, reported engaging in many more activities than their African American, Latino, American Indian, and low-income classmates. The activities they choose also tend to feature more leadership roles and confer more honors, both of which could help win a university slot.

If race, test scores, and extracurriculars are reduced in prominence, however, it’s difficult to say what will take their place. Separate campaigns have been waged against the use of admissions essays, which have been found to favor wealthier students, and undergraduate letters of admission, which often leverage social capital that disadvantaged kids don’t have. In the end, admissions officers might be left throwing darts at the wall.

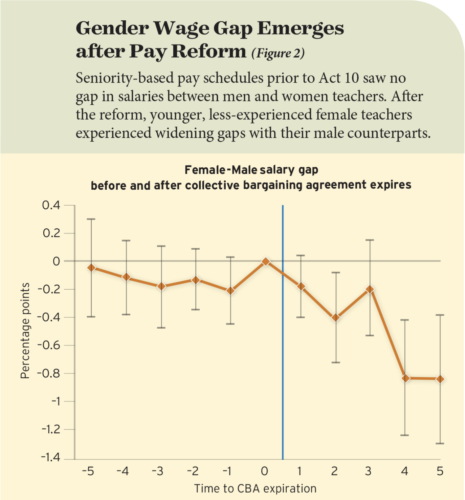

Flexible pay has unintended consequences

The Act 10 legislation, passed in 2011 by Wisconsin Republicans, ignited one of the most furious school reform controversies of its era. By stripping teachers of the right to collectively bargain over salary schedules and benefits, then-Gov. Scott Walker dealt a massive blow to teachers’ unions, perhaps the most influential progressive force in state politics. It was also a provocation that some credit with catalyzing the revived organizing movement of the last half-decade, which has seen a rash of teacher strikes and renewed hostility to other planks of the reform agenda.

In a study published in the education journal Education Next, Yale economist Barbara Biasi looked at the transformative effects of Act 10 on teacher labor markets, which suddenly became much more flexible as schools could opt to pay different salaries to teachers on the basis of either career tenure or classroom performance. That had some positive effects for individual districts: Younger, more effective teachers were able to win large pay increases by moving to areas where their lack of seniority wasn’t held against them.

But the state also saw an unpalatable side effect. In part because younger female teachers are more reluctant than their male counterparts to negotiate aggressively for higher pay, flexible-pay districts also saw a newfound gender wage gap begin to open. Though small on average, Biasi found that the cumulative effect over a teacher’s career could amount to an entire year’s pay.

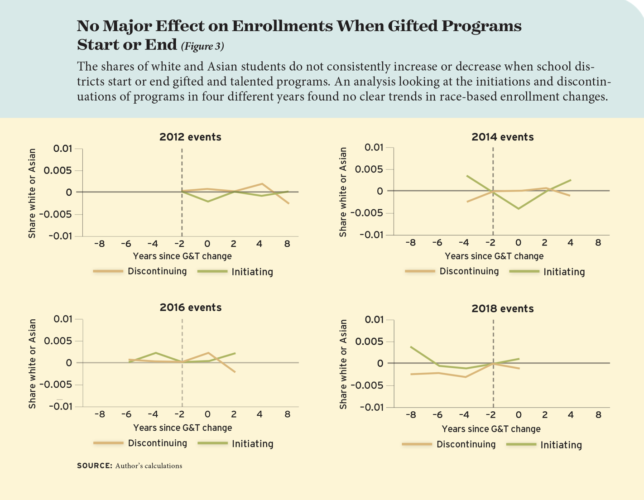

Gifted education does little to increase segregation

The last few years have brought a clash between advocates for educational equity and proponents of gifted education. That battle — over gifted programs’ place in the K–12 portfolio, and whether all kids truly have access to them — has largely played out in major urban districts like New York and San Francisco, where both prestigious exam schools and accelerated learning more generally have been criticized for their disproportionately tiny number of seats offered to Hispanic and African American pupils.

But several studies recently emerged that tell a different story. One, published in Education Next by Williams College economist Owen Thompson, examines the effect of K–6 gifted programs on the racial makeup of kindergarten and elementary classrooms. Examining enrollment information for nearly 47,000 public schools around the United States, Thompson found that the special sections are disproportionately made up of white and Asian students. But because they are so small in scope, they make a negligible impact on the overall demographics of the schools in which they are housed. In fact, eliminating every such program would not significantly change the exposure of different student groups to one another.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that gifted learning opportunities can’t be made available to more kids, however. And a separate paper, by NWEA researchers, suggests that the key to welcoming more English learners and students with disabilities into accelerated classrooms is for states to enact formal mandates related to the provision of gifted services, require districts to maintain their own formal gifted plans, and regularly audit them for compliance.