This the first in a series of weekly analyses of COVID-19 policies in 100 large and high-profile school systems, produced by the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington, Bothell.

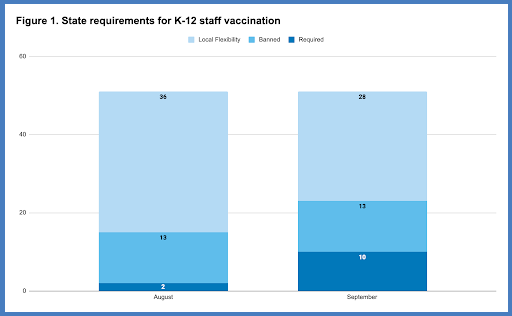

President Joe Biden’s push for more employers to require vaccines is likely to accelerate an already-growing trend in schools.

In the past month, the number of states requiring teacher vaccinations has jumped to 10, including the District of Columbia, according to a new analysis we conducted at the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Those include roughly a third (31) of the districts in our review of 100 large and high-profile school systems. And Los Angeles Unified’s high-profile move to require eligible students to get vaccinated suggests vaccine mandates won’t be confined to school employees.

Rising vaccination rates are good news for the country’s students. They increase the chances schools will be able to keep them safe, and keep them learning, all year and in person as much as possible.

But they won’t totally eliminate other challenges school systems are likely to face. Clarifying quarantine rules, and supporting high-quality instruction for students who are forced to quarantine or isolate because they’ve tested positive or been exposed to the virus, remains a critical task for state and school district leaders.

Right now, the amount of time students can expect to spend in quarantine if they are suspected of being exposed to the virus, and the amount of instruction they can expect to receive, varies a lot depending on where they live.

State quarantine and isolation policies leave districts hanging

Forty-three states and D.C. have updated their quarantine and isolation guidelines for the 2021-22 school year, while seven states offer no guidance and simply link to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webpage.

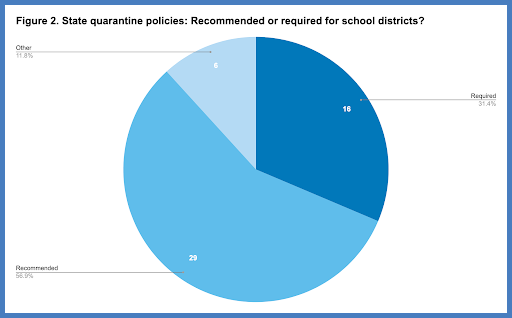

In 15 states and D.C., schools and districts must follow statewide quarantine guidance, while 29 states offer only recommended guidance. The remaining six states provide very little. The Iowa Department of Public health, for example, stated that it is “not currently issuing isolation or quarantine orders for COVID-19 positive or COVID-19 exposed individuals.”

Half of the states provide detailed guidance about how long a student should spend in quarantine. Of these, 14 specify isolation periods that range from seven to 14 days for different categories of exposure, and 11 specify periods that range from seven to 10 days.

The other half of states give school districts broad flexibility to determine the number of days students and staff are expected to quarantine, depending on whether they are asymptomatic, vaccinated or have a negative COVID-19 test.

The result of this loose, varied and minimal state guidance is a wide range of district quarantine policies.

Alaska’s Anchorage School District allows up to 24 quarantine days for students who live with an infected household member and cannot avoid continued close contact. At the other extreme, Kansas’s Wichita Public Schools allows exposed students to return to class immediately, provided they wear a mask for 14 days and take daily rapid antigen tests for eight days.

The shortest quarantines are heavily concentrated in Florida, where seven of eight districts in our review allow students to return as early as two to five days after exposure. Miami-Dade County Public Schools, which requires a 10-day quarantine, is the exception. Florida state guidance recommends four to seven days of isolation.

When will students and teachers have to quarantine? For how long? It depends

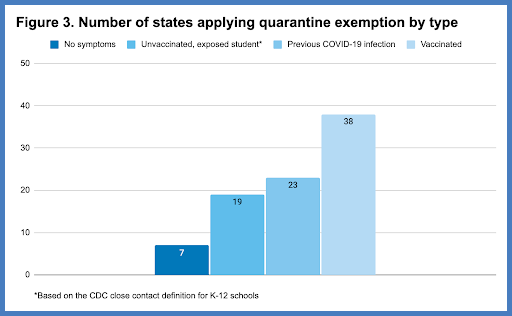

Most states have at least some policies that ease quarantine requirements for students who meet certain criteria.

Thirty-eight states exempt fully vaccinated students from quarantines, 23 provide exemptions if an individual has previously been diagnosed with COVID-19 and 7 exempt individuals if they are asymptomatic. In addition, 19 states include the CDC’s revised definition of “close contact” for K-12 settings to determine whether a student counts as having been exposed to the virus.

Easing quarantine rules for vaccinated people can reduce unnecessary learning disruptions and create an incentive to get vaccinated that stops short of a mandate. But some states have tied districts’ hands.

In Montana, a state law prohibiting people from being treated differently based on vaccination status means that local leaders cannot use it as a way to shorten quarantines. In Ohio, a state law outlines “anti-discrimination” practices that would prohibit schools from establishing safety precautions specifically for unvaccinated individuals.

Some states devised creative guidance to keep teachers and students in schools as much as possible. The Mississippi State Department of Health allows for teachers and staff deemed “essential” to keep working if they remain asymptomatic, wear a mask at all times, self-monitor for symptoms and self-quarantine at home when they are not at work. In Utah, local health departments and districts can offer students the option to wear a mask at school for 10 days in place of following quarantine-at-home protocols.

How will students in quarantine continue learning?

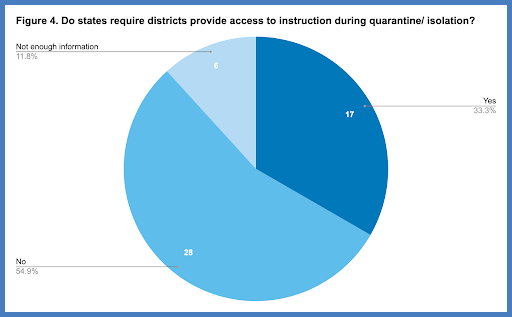

Remote learning is a critical tool for keeping students learning during quarantine, but not all students will have access. Eight states — Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Tennessee and Texas — are restricting at least one aspect of remote learning.

In some cases, states outlined these restrictions in their American Rescue Plan documents, which were created before the Delta variant started rampaging across the country. For example, New Jersey states that, “In the 2021-22 school year, if buildings are open for in-person instruction, parents or guardians will not be able to opt their child out of in-person instruction.”

Only 17 states have stated they will require districts to ensure that students can access instruction during quarantine or isolation.

Some provide detailed guidance in their 2021 reopening plans about how districts should provide remote learning. South Dakota explains that schools opting to provide long-term virtual options must commit to quality instruction, state-aligned standards and certified, well-trained staff. The Illinois State Board of Education spelled out details about instructional time and enrollment.

Five districts of the 100 we reviewed — Boulder Valley, Colorado; Houston ISD; Kansas City Public Schools; Metro Nashville; and San Diego Unified — are offering their remote learning program, or an equivalent, to quarantined students. The rest will likely rely on schools and teachers to create their own solutions — which, again, means the education students will receive could vary a lot depending on where they live.

Chicago Public Schools expects teachers to provide coursework aligned to the instruction students would have received in class, and for students to receive up to two hours of live, real-time teaching a day while they’re in quarantine.

In Miami-Dade County Public Schools, teachers will be expected to revive a practice from last year: concurrent instruction, in which some students join class by videoconference while others attend in person.

Vermont’s Champlain Valley Public Schools distinguish between individually quarantined students and whole-class quarantines. The district will provide remote instruction only if the entire class must quarantine. Otherwise, quarantines will be treated as regular absences, and students won’t receive instruction.

Most states back COVID-19 testing

The majority of states — 36, as well as D.C. — provide schools and districts with both guidance and funding to administer COVID-19 testing. A robust initiative from the Washington State Department of Health, Learn to Return, helps schools provide vaccines and tests.

The remaining 14 states provide either limited or no information about statewide COVID-19 testing. In the “Interim Guidance for COVID-19 Prevention in Virginia PreK-12 Schools,” testing is mentioned as one of nine key prevention strategies. However, there is no reference to statewide support for districts that wish to establish and run these programs.

This month, a new type of policy, known as test-to-stay, has emerged to limit major school-based outbreaks.

Under Utah’s recommended policy, if 30 students, or 2 percent of a school’s student body — whichever is lower — test positive for COVID-19, the school will screen all students. Those who test positive will be required to isolate at home, but those whose results are negative can continue in-person classes.

In Washington, schools can opt in to a test-to-stay protocol in which someone who comes into close contact with an individual testing positive for COVID-19 can receive a negative test and continue to attend classes, but quarantine from all extracurriculars and other activities.

These policies can help catch outbreaks before they spread out of control. But they also underscore the importance of providing instruction to students who are asked to stay home.

Vaccinations necessary but not sufficient

States and districts received a historic infusion of federal COVID relief dollars with the charge to keep kids safe and learning through the 2021-22 school year.

However, emerging fall trends reveal that states’ plans are underwhelming and largely miss the mark. Policymakers and education leaders can shift course to ensure students are safe and learning this fall and beyond by reinforcing the things that work:

- Provide districts support for coordinated vaccination and COVID-19 testing. States can give districts a framework to increase vaccinations among staff and students while implementing robust testing programs to catch potential outbreaks. For example, state education and health agencies can develop a network of local health authorities who can facilitate both vaccination and testing in schools.

- Develop a sense of safety by reporting staff vaccination coverage. A fully vaccinated education workforce across a state will protect students who are not eligible to be vaccinated and limit learning disruptions. Many states publish COVID-19 vaccination rates for health care professionals by county on public dashboards to establish transparency and trust among those who visit care facilities. Reporting similar data for teachers would help develop a sense of safety for parents and students.

- Establish clear, easy-to-follow quarantine rules. Differing federal, state and local policies on quarantine and isolation leave parents and students confused and uncertain about what is safe and what to do next. States can establish clear, straightforward quarantine policies along with streamlined communications efforts to ensure students, teachers and families feel secure about school safety precautions and reduce guesswork for local education leaders.

- Ensure students have access to remote learning throughout the year.States must set clear expectations about enrollment, attendance and quality of remote learning. With many competing priorities, districts need state support to ensure schools are providing high-quality remote instruction to students in quarantine or isolation.

These measures demand stronger action by state leaders. Students cannot afford to lose days or weeks of instruction while school district administrators navigate vague, conflicting or counterproductive guidance from other layers of government.