Listen to Christina Cipriano read her essay, produced by Julie Depenbrock on the original link.

“Don’t stare, Hannah!”

Those were the scolding words a parent yelled as she hurried her 6-year-old away from us on the soccer field.

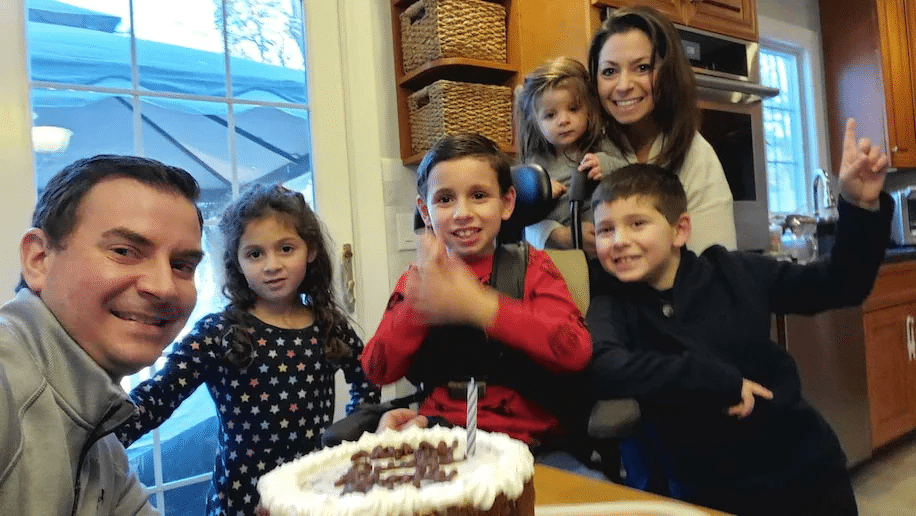

My family was still gathering to leave. With four young children, we’re always the last to leave. On this day, we’d been living the suburban dream, having walked to the field — my 9-year-old son, Miles, on his adaptive Rifton bike. It’s rather magical as far as adaptive equipment goes: wheelchair meets tricycle meets stroller meets Transformer. Our younger three kids think it’s cool. No wonder Hannah was staring.

To be clear, I had no problem with Hannah’s behavior. But her mother’s reprimand? It made me sick to my stomach. I, too, was raised being told not to stare, and I recognize that the expression doesn’t come from a place of malice. But the words hurt more now than they did before.

Miles has Phelan-McDermid Syndrome (PMS), a rare genetic disorder caused by a deletion or mutation on the q arm of chromosome 22. The more than 2,800 people in the world with PMS are often diagnosed with autism, have severe cognitive disabilities, are nonverbal, and have seizures and sleep disorders, among many other behavioral and medical challenges. As our son ages, he loses skills. I counter this loss by showing old videos to new care providers to make sure they see him and hear the beautiful voice this horrid disease took away. The covid-19 pandemic forced us to make our small world smaller. It was only when we started venturing back into socialization that I was struck by the parenting of the staring.

Let’s consider why kids stare in the first place.

Our brains are wired to organize our experiences into patterns as we age. By adulthood, these patterns of understanding are fully formed and can be difficult to unlearn. (This is one reason it’s so hard for people to recognize structural racism or ableism; when education and society have conditioned them to believe one thing, it can be difficult to adapt to a new way of seeing.)

But for children, each new experience is an opportunity to evolve. Children who stare are curious. A child who is staring is learning.

So, what are adults teaching when we tell children to look away? Do we say “don’t stare” in the interest of respecting boundaries, or do we say it to create them? Are we teaching children to recoil from those who are different from them? What are we afraid they will see?

Over time I’ve come to perceive essentially three kinds of parents: There are the parents who say “don’t stare,” like Hannah’s mom, and disengage. Are they concerned about what their child might say? Maybe they themselves don’t know what to say? There are the parents who stare, too, and never speak to us. We hear their silence loudly. It says: You are less than us. We might live in the same neighborhood, but we are not the same.

And then there are the parents who lean into the staring. I personally love these parents. They ask their child what they see. They exchange warm smiles and speak to our son as they would to any other child.

So to the well-intentioned parents who tell your kids not to stare: I encourage you to rethink this approach.

Three hundred million people, including my son, have a rare disease. Most disabilities, however, are not as rare. Down syndrome, for example, is among the most physically recognizable chromosomal disorders and is the most prevalent, occurring in 1 of every 700 births in the United States. And roughly 7 million students with disabilities (ages 3 to 21) are educated in the U.S. public school system.

We can’t expect our children to embrace differences and learn together if we fail to teach them how. So when you see a child staring at someone who is different from them, take that as an invitation to show the other person that you see them — with a wave, a question or a a smile.

You can support your child by saying: I see you’re staring. What questions do you have?

Parents can model humanity and, with their children, develop scripts of what to say in the name of healthy inquiry: My name is … What’s your name?

You can direct your child to find something in common to open a conversation: That’s a cool bike. I like to ride my bike, too!

Or you can be direct with the person your child is staring at and introduce your child to help them make a connection: My child is curious to learn about you and your bike. This is his name, and he likes to ride his bike, too.

Inclusion requires actively including everyone. Anything less is merely performative.

We know you see us. And we see you, too. Let’s start with hello.